Deep Dive into the Kubernetes Scheduler Framework

This is the second in a series of blog posts exploring the Kubernetes kube-scheduler from the perspective of someone who has dug deep into the codebase.

Introduction

In my previous post, I introduced the plugin-first architecture of the Kubernetes scheduler. Today, I want to dive deep into the Plugin Framework, the core component that makes the scheduler truly extensible.

The Framework is where the scheduler’s extensibility truly shines. It’s not just a simple plugin loader; it’s an orchestration system that manages plugin lifecycles and execution order across multiple extension points. Understanding how this works is crucial for anyone who wants to extend scheduler behavior or simply understand how the scheduler makes its decisions.

1. Plugin Framework Architecture Overview

The framework provides a structured lifecycle where plugins can interact with each other, share data, and influence scheduling decisions at well-defined extension points.

The framework orchestrates plugins at various extension points throughout the scheduling process, allowing for customization of scheduling behavior. It includes a Plugin Registry and supports 12 distinct extension points, each serving a specific purpose in the scheduling pipeline.

Scheduler Plugins Framework: Architecture Overview

The following diagram illustrates how the framework organizes plugins and extension points, showing the complete flow from plugin registry to execution:

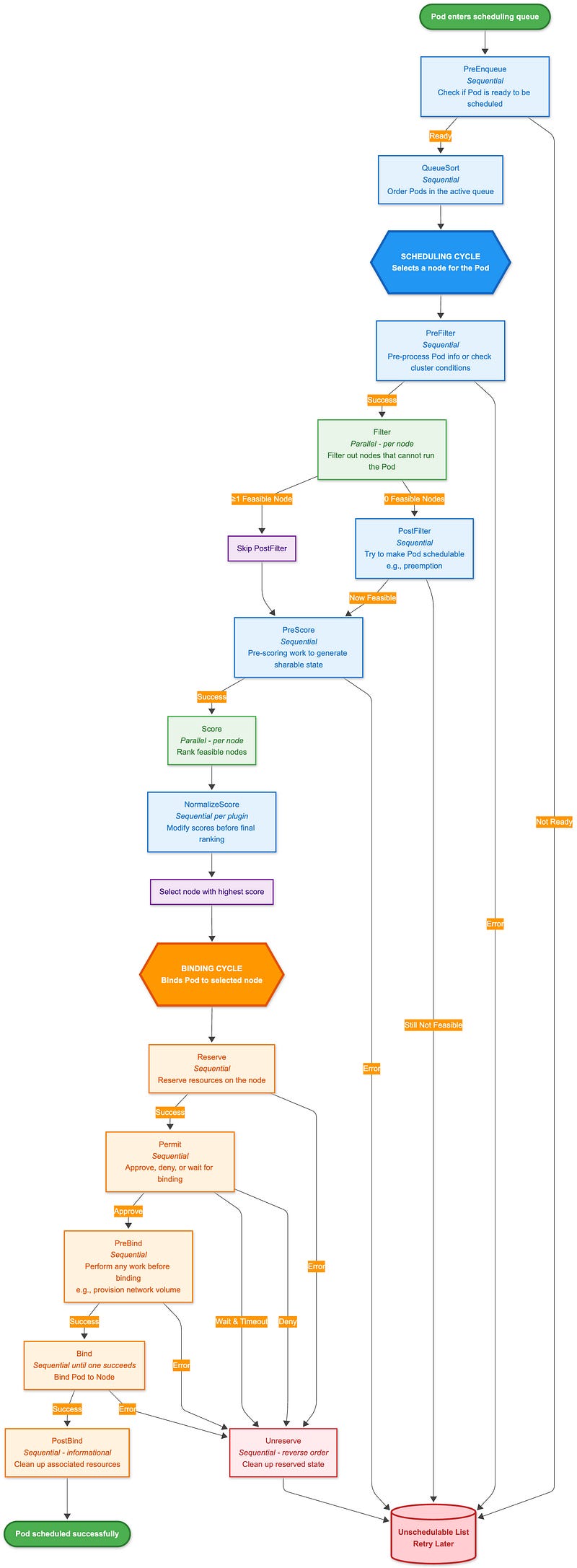

Scheduling Cycle (Blue boxes)

Runs synchronously to select a node for the Pod:

Sequential phases (darker blue): Execute plugins one by one (PreFilter, PostFilter, PreScore, NormalizeScore)

Parallel phases (lighter green): Execute plugins concurrently across nodes (Filter, Score)

Binding Cycle (Orange boxes)

Can run asynchronously to bind the Pod to the selected node. All phases execute sequentially except Bind, which stops at the first successful plugin.

In addition to:

Error handling: Most failures lead to the Unschedulable list, triggering Unreserve for cleanup

PostFilter bypass: Only runs when no feasible nodes are found (e.g., for preemption)

Permit gate: Can delay binding or reject it after reservation

CycleState: Flows through the entire cycle, allowing plugins to share data (see Section 8)

2. Extension Points: The Scheduler’s Decision Pipeline

The framework defines 12 distinct extension points, each serving a specific purpose in the scheduling pipeline. These extension points form a timeline that guides pods through the scheduling process. The interface can be found in`pkg/scheduler/framework/interface.go`. Let’s walk through each one:

PreEnqueue Plugins

type PreEnqueuePlugin interface {

Plugin

PreEnqueue(ctx context.Context, p *v1.Pod) *fwk.Status

}PreEnqueue plugins are called before pods are added to the active queue. This is the earliest point where plugins can influence scheduling. The framework documentation emphasizes that these plugins should be lightweight and efficient, as they run in event handlers and could block other pods’ enqueuing.

What’s interesting about this extension point is that it’s designed for quick checks that can prevent unnecessary work. For example, a plugin might check if a pod has required annotations or wheather certain cluster conditions are met before allowing it into the scheduling queue.

2. QueueSort Plugins

type QueueSortPlugin interface {

Plugin

Less(fwk.QueuedPodInfo, fwk.QueuedPodInfo) bool

}QueueSort plugins determine the order in which pods are processed from the scheduling queue. Only one queue sort plugin can be enabled at a time because having multiple sorting plugins would create conflicting ordering logic, you can’t have pods sorted by both priority and creation time simultaneously.

The default implementation uses pod priority and creation time, but custom implementations could consider factors such as resource requirements, deadlines, or business logic.

3. PreFilter Plugins

type PreFilterPlugin interface {

Plugin

// PreFilter is called at the beginning of the scheduling cycle.

// It returns PreFilterResult which may influence what or how many nodes to evaluate downstream.

PreFilter(ctx context.Context, state CycleState, p *v1.Pod, nodes []NodeInfo) (*PreFilterResult, *Status)

// PreFilterExtensions returns a PreFilterExtensions interface if the plugin implements one,

// or nil if it does not.

PreFilterExtensions() PreFilterExtensions

}PreFilter plugins run before the filtering phase and are perfect for expensive computations that can be reused across multiple nodes. This is where plugins typically compute data that will be used by Filter plugins. They are responsible for:

Receives all nodes being considered for scheduling

Can return a `PreFilterResult` to limit which nodes are evaluated by Filter plugins

Can return `Skip` status to skip both this PreFilter and its coupled Filter plugin

The `PreFilterExtensions` interface allows plugins to provide additional functionality:

AddPod: Called when a pod is added to a node

RemovePod: Called when a pod is removed from a node

This is particularly useful for plugins that need to track pod-to-pod relationships or maintain state across multiple scheduling attempts.

4. Filter Plugins

type FilterPlugin interface {

Plugin

Filter(ctx context.Context, state fwk.CycleState, pod *v1.Pod, nodeInfo fwk.NodeInfo) *fwk.Status

}Filter plugins are the core of the scheduling decision process. They determine whether a specific node can accommodate a pod. If any filter plugin returns a non-success status, the node is eliminated from consideration.

The framework runs filter plugins in parallel across nodes, which is crucial for performance. Each plugin receives the same `CycleState` and can access data computed by PreFilter plugins.

5. PostFilter Plugins

type PostFilterPlugin interface {

Plugin

// PostFilter is called when the scheduling cycle failed at PreFilter or Filter.

// NodeToStatusReader has statuses that each Node got in PreFilter or Filter phase.

// A PostFilter plugin should return one of the following statuses:

// - Unschedulable: the plugin gets executed successfully but the pod cannot be made schedulable.

// - Success: the plugin gets executed successfully and the pod can be made schedulable.

// - Error: the plugin aborts due to some internal error.

PostFilter(ctx context.Context, state CycleState, pod *v1.Pod, filteredNodeStatusMap NodeToStatusReader) (*PostFilterResult, *Status)

}PostFilter plugins run when no nodes pass the filtering phase. This is typically where preemption logic lives. The plugin receives information about why each node was filtered out and can attempt to make the pod schedulable by preempting other pods. They are responsible for:

Called only when PreFilter or Filter phases fail with Unschedulable or UnschedulableAndUnresolvable

Can return `PostFilterResult` with a nominated node name for preemption

Informational plugins should be configured first and return Unschedulable status

The default preemption plugin evaluates multiple preemption strategies and selects the best one based on various criteria.

6. PreScore Plugins

type PreScorePlugin interface {

Plugin

// PreScore is called by the scheduling framework after a list of nodes

// passed the filtering phase. All prescore plugins must return success or

// the pod will be rejected.

// When it returns Skip status, coupled Score plugin will be skipped.

PreScore(ctx context.Context, state CycleState, pod *v1.Pod, nodes []NodeInfo) *Status

}PreScore plugins run before the scoring phase, similar to how PreFilter plugins work before filtering. They’re perfect for computations that will be reused across multiple Score plugins. They are responsible for:

Receives all nodes that passed the filtering phase

Can return `Skip` status to skip the coupled Score plugin

All PreScore plugins must return success, or the pod will be rejected

7. Score Plugins

type ScorePlugin interface {

Plugin

// Score is called on each filtered node. It must return success and an integer

// indicating the rank of the node. All scoring plugins must return success or

// the pod will be rejected.

Score(ctx context.Context, state CycleState, p *v1.Pod, nodeInfo NodeInfo) (int64, *Status)

// ScoreExtensions returns a ScoreExtensions interface if it implements one, or nil if it does not.

ScoreExtensions() ScoreExtensions

}Score plugins rank nodes that passed the filtering phase. Each plugin returns a score between `MinNodeScore` and `MaxNodeScore`, and the framework combines these scores using weighted averages.

The `ScoreExtensions` interface provides normalization functionality, allowing plugins to adjust their scores based on the range of scores across all nodes.

8. Reserve Plugins

type ReservePlugin interface {

Plugin

Reserve(ctx context.Context, state fwk.CycleState, p *v1.Pod, nodeName string) *fwk.Status

Unreserve(ctx context.Context, state fwk.CycleState, p *v1.Pod, nodeName string)

}Reserve plugins are called when a pod is tentatively assigned to a node. This is where plugins can “reserve” resources or perform other actions that need to be undone if scheduling fails later.

The `Unreserve` method is called if scheduling fails after reservation, allowing plugins to clean up any state they created.

9. Permit Plugins

type PermitPlugin interface {

Plugin

Permit(ctx context.Context, state fwk.CycleState, p *v1.Pod, nodeName string) (*fwk.Status, time.Duration)

}Permit plugins can approve, reject, or delay pod binding. This is the last chance for plugins to prevent a pod from being bound to a node. They can also return a timeout, causing the pod to wait before binding.

This extension point is particularly interesting because it allows for sophisticated scheduling policies like gang scheduling or resource quotas.

10. PreBind Plugins

type PreBindPlugin interface {

Plugin

// PreBindPreFlight is called before PreBind, and the plugin is supposed to return Success, Skip, or Error status.

// If it returns Success, it means this PreBind plugin will handle this pod.

// If it returns Skip, it means this PreBind plugin has nothing to do with the pod, and PreBind will be skipped.

// This function should be lightweight, and shouldn’t do any actual operation.

PreBindPreFlight(ctx context.Context, state CycleState, p *v1.Pod, nodeName string) *Status

// PreBind is called before binding a pod. All prebind plugins must return

// success or the pod will be rejected and won’t be sent for binding.

PreBind(ctx context.Context, state CycleState, p *v1.Pod, nodeName string) *Status

}PreBind plugins run just before the pod is bound to the node. This is where plugins can perform final preparations, such as creating necessary resources or updating external systems. They are responsible for:

`PreBindPreFlight` is a lightweight check executed first to determine if the plugin should handle the pod

`PreBind` performs the actual pre-binding work (e.g., provisioning volumes)

All PreBind plugins must return success, or binding will be aborted

11. Bind Plugins

type BindPlugin interface {

Plugin

// Bind plugins will not be called until all pre-bind plugins have completed.

// Each bind plugin is called in the configured order. A bind plugin may choose

// whether or not to handle the given Pod. If a bind plugin chooses to handle a Pod,

// the remaining bind plugins are skipped. If a bind plugin chooses not to handle

// a pod, it must return Skip in its Status code.

Bind(ctx context.Context, state CycleState, p *v1.Pod, nodeName string) *Status

}Bind plugins handle the actual binding of the pod to the node. The default implementation updates the pod’s `.spec.nodeName` field, but custom implementations could handle more complex binding scenarios. They are responsible for:

Calling in order; first plugin to return Success handles binding

Must return `Skip` if choosing not to handle the pod

Remaining bind plugins are skipped once one returns Success

12. PostBind Plugins

type PostBindPlugin interface {

Plugin

PostBind(ctx context.Context, state fwk.CycleState, p *v1.Pod, nodeName string)

}PostBind plugins run after successful binding. This is typically used for cleanup, logging, or updating external systems.

3. Plugin Lifecycle

The plugin lifecycle describes the end-to-end plugin instances within the scheduler. Understanding it is critical because plugins are created once but used millions of times. A single `NodeResourcesFit` plugin instance created at scheduler startup will evaluate every pod scheduled for the entire lifetime of the scheduler, potentially millions of pods over days or weeks.

Let’s trace the complete journey of a plugin from code to execution.

Phase 1: Registering the Plugin (Build Time → Scheduler Startup)

Before the scheduler can use any plugin, it must be **registered** in a global registry. This happens at scheduler startup when the registry is built.

Every plugin in Kubernetes is represented by a factory function with this exact signature:

// PluginFactory is a function that creates a plugin instance

type PluginFactory = func(ctx context.Context, args runtime.Object, f Handle) (Plugin, error)

...

// Registry maps plugin names to their factory functions

type Registry map[string]PluginFactoryThe factory function is what actually creates plugin instances. Let’s look at the real in-tree plugin registry:

func NewInTreeRegistry() runtime.Registry {

fts := plfeature.NewSchedulerFeaturesFromGates(feature.DefaultFeatureGate)

registry := runtime.Registry{

“DynamicResources”: runtime.FactoryAdapter(fts, dynamicresources.New),

“ImageLocality”: imagelocality.New,

“TaintToleration”: runtime.FactoryAdapter(fts, tainttoleration.New),

“NodeName”: runtime.FactoryAdapter(fts, nodename.New),

“NodePorts”: runtime.FactoryAdapter(fts, nodeports.New),

“NodeAffinity”: runtime.FactoryAdapter(fts, nodeaffinity.New),

“PodTopologySpread”: runtime.FactoryAdapter(fts, podtopologyspread.New),

“NodeUnschedulable”: runtime.FactoryAdapter(fts, nodeunschedulable.New),

“NodeResourcesFit”: runtime.FactoryAdapter(fts, noderesources.NewFit),

...

}

return registry

}The `Registry` is simply a map: `map[string]PluginFactory`. Plugin name → Factory function.

For out-of-tree (custom) plugins, you create your own registry and merge it:

// Custom plugin registration

customRegistry := runtime.Registry{

“MyCustomPlugin”: myplugin.New,

}

// Merge with in-tree plugins

inTreeRegistry := plugins.NewInTreeRegistry()

inTreeRegistry.Merge(customRegistry)At this phase, no plugins exist yet, only factory functions that know how to create them.

Phase 2: Plugin Instantiation (Framework Initialization)

When the scheduler starts, `NewFramework()` is called for each scheduler profile. This is where plugins actually get created:

func NewFramework(ctx context.Context, r Registry, profile *KubeSchedulerProfile) (Framework, error) {

// ... setup code ...

f := &frameworkImpl{

registry: r,

pluginsMap: make(map[string]fwk.Plugin),

preFilterPlugins: []fwk.PreFilterPlugin{},

filterPlugins: []fwk.FilterPlugin{},

scorePlugins: []fwk.ScorePlugin{},

// ... other extension point slices ...

}

// Step 1: Determine which plugins are needed

// Only plugins configured in the profile are instantiated

pluginsNeeded := f.pluginsNeeded(profile.Plugins)

// Step 2: Build configuration map

pluginConfig := make(map[string]runtime.Object, len(profile.PluginConfig))

for i := range profile.PluginConfig {

name := profile.PluginConfig[i].Name

pluginConfig[name] = profile.PluginConfig[i].Args

}

// Step 3: Instantiate each needed plugin

for name, factory := range r {

// Skip plugins not in the profile configuration

if !pluginsNeeded.Has(name) {

continue

}

// Get plugin-specific configuration (may be nil)

args := pluginConfig[name]

// Call the factory function to create the plugin instance

p, err := factory(ctx, args, f)

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf(”initializing plugin %q: %w”, name, err)

}

// Store the plugin instance in the map

f.pluginsMap[name] = p

}

// Step 4: Organize plugins into extension point slices

// This groups plugins by which interfaces they implement

for _, e := range f.getExtensionPoints(profile.Plugins) {

if err := updatePluginList(e.slicePtr, *e.plugins, f.pluginsMap); err != nil {

return nil, err

}

}

return f, nil

}Phase 3: Per-Cycle Execution (The Scheduling Loop)

Now the plugins are alive, and the scheduler enters its main loop, processing one pod at a time. This is where plugin instances are actually called:

func (sched *Scheduler) ScheduleOne(ctx context.Context) {

// Step 1: Get next pod from queue

podInfo, err := sched.NextPod(logger)

pod := podInfo.Pod

// Step 2: Get the framework for this pod

fwk, err := sched.frameworkForPod(pod)

// Step 3: Create a NEW CycleState for THIS scheduling attempt

state := framework.NewCycleState()

// Step 4: Run the scheduling cycle

scheduleResult, err := sched.SchedulePod(ctx, fwk, state, pod)

// Step 5: Run the binding cycle

// ...

}Inside SchedulePod, plugins are called in sequence:

// Simplified scheduling cycle

func (sched *Scheduler) SchedulePod(ctx context.Context, fwk framework.Framework, state *CycleState, pod *v1.Pod) (ScheduleResult, error) {

// PREFILTER: Run sequentially

for _, pl := range fwk.preFilterPlugins {

status := pl.PreFilter(ctx, state, pod)

if !status.IsSuccess() {

return ScheduleResult{}, status.AsError()

}

}

// FILTER: Run in parallel across nodes

feasibleNodes := fwk.RunFilterPluginsWithNominatedPods(ctx, state, pod, nodes)

// SCORE: Run in parallel across nodes

scores, status := fwk.RunScorePlugins(ctx, state, pod, feasibleNodes)

// Select best node

bestNode := selectHost(scores)

return ScheduleResult{SuggestedHost: bestNode}, nil

}Here, the real parallel execution:

func (f *frameworkImpl) RunScorePlugins(ctx context.Context, state *CycleState, pod *v1.Pod, nodes []*NodeInfo) ([]NodePluginScores, *Status) {

// Run Score method for each node in PARALLEL

f.Parallelizer().Until(ctx, len(nodes), func(index int) {

nodeInfo := nodes[index]

// For this node, run ALL score plugins

for _, pl := range f.scorePlugins {

score, status := pl.Score(ctx, state, pod, nodeInfo.Node().Name)

if !status.IsSuccess() {

// Handle error

return

}

// Store score

pluginToNodeScores[pl.Name()][index] = score

}

})

return scores, nil

}Key Lifecycle Properties:

Plugin instances are reused: The same plugin instance created at startup is called for every pod

CycleState is fresh: Each scheduling cycle gets a new `CycleState` for isolation

Plugins must be thread-safe: During Filter/Score, the same plugin instance is called from multiple goroutines simultaneously

No per-cycle initialization: Plugins don’t have an `Initialize()` method called before each cycle

Phase 4: Plugin State Management (Instance vs Cycle State)

Because plugins are singletons reused across millions of cycles, managing state correctly is critical:

Instance-Level State (Persists Forever): State stored in plugin struct fields lives for the entire scheduler lifetime

type Fit struct {

handle framework.Handle // Reused across all cycles

ignoredResources sets.Set[string] // Immutable config

enableInPlacePodVerticalScaling bool // Feature gate

resourceAllocationScorer resourceAllocationScorer // Scoring logic

// If you add mutable state, you MUST use locks:

mu sync.RWMutex

cache map[string]interface{} // Protected by mu

}Cycle-Level State (Lives for One Pod): Data that’s specific to a single scheduling cycle goes in `CycleState`

const preFilterStateKey = “PreFilter” + Name

type preFilterState struct {

podRequest *framework.Resource // Resources requested by the pod being scheduled

}

func (pl *Fit) PreFilter(ctx context.Context, cycleState *framework.CycleState, pod *v1.Pod) *framework.Status {

// Compute resource requests ONCE

podRequest := computePodResourceRequest(pod)

// Store in CycleState for Filter phase to read

cycleState.Write(preFilterStateKey, &preFilterState{

podRequest: podRequest,

})

return nil

}

func (pl *Fit) Filter(ctx context.Context, cycleState *framework.CycleState, pod *v1.Pod, nodeInfo *framework.NodeInfo) *framework.Status {

// Read the pre-computed data

s, err := cycleState.Read(preFilterStateKey)

if err != nil {

return framework.AsStatus(err)

}

state := s.(*preFilterState)

// Use it to check if the node has enough resources

if nodeInfo.Allocatable().MilliCPU < state.podRequest.MilliCPU {

return framework.NewStatus(framework.Unschedulable, “insufficient CPU”)

}

return nil

}Which means:

PreFilter runs once per pod

Filter runs N times per pod (once per node)

Without CycleState, you’d recompute pod resources N times

With CycleState, you compute once and read N times

Phase 5: Shutdown and Cleanup

The `Plugin` interface doesn’t define `Initialize()` or `Close()` methods. However, plugins can listen for scheduler shutdown via the context:

func New(ctx context.Context, args runtime.Object, h framework.Handle) (framework.Plugin, error) {

pl := &MyPlugin{

handle: h,

stopCh: make(chan struct{}),

}

// Start background workers if needed

go pl.backgroundWorker(ctx)

// Listen for shutdown

go func() {

<-ctx.Done() // Scheduler is shutting down

close(pl.stopCh)

pl.cleanup()

}()

return pl, nil

}

func (pl *MyPlugin) backgroundWorker(ctx context.Context) {

ticker := time.NewTicker(time.Minute)

defer ticker.Stop()

for {

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

return

case <-pl.stopCh:

return

case <-ticker.C:

// Do periodic work

}

}

}

func (pl *MyPlugin) cleanup() {

// Close connections

// Flush metrics

// Clear caches

}This lifecycle design is why Kubernetes scheduler can handle thousands of pods per second with sub-second latency, even in clusters with thousands of nodes.

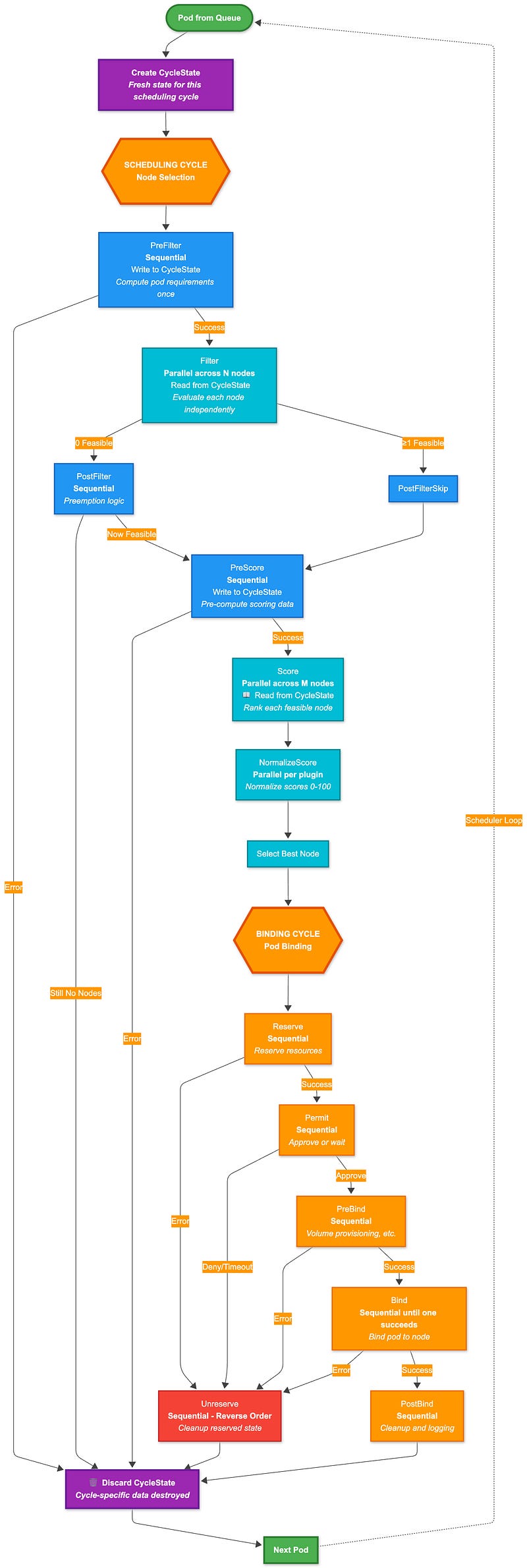

4. The Scheduling Cycle: Timeline and Execution

From my observation of how the scheduler works, it’s clear that the 12 extension points form a well-defined timeline that a pod follows during scheduling. What really stands out is how the framework manages plugin execution. It smartly balances performance and correctness by running some plugins sequentially and others in parallel, depending on what each phase allows.

PreFilter → Filter (parallel) → PostFilter → PreScore → Score (parallel) → NormalizeScore (parallel) → Reserve → Permit → PreBind → Bind → PostBind → Unreserve

This timeline highlights several key characteristics:

Filter and Score are typically the most time-consuming phases, evaluating all available nodes

Permit can introduce a `Wait` state, allowing plugins to delay binding for sophisticated scheduling policies

Unreserve provides cleanup functionality if scheduling fails at any point after reservation

The cycle is designed to be deterministic and consistent, ensuring all plugins see the same cluster state

Sequential vs Parallel Execution

The framework carefully chooses which phases execute sequentially and which can run in parallel:

Sequential Execution Phases

The following extension points execute plugins sequentially (one after another):

PreEnqueue: Sequential execution ensures proper ordering of queue admission decisions

QueueSort: Only one sort plugin can be enabled, as multiple would conflict

PreFilter: Sequential execution ensures PreFilter plugins see consistent state and can build upon each other’s computations

PostFilter: Preemption logic must execute sequentially to maintain consistency

5. PreScore: Sequential execution ensures all nodes see the same computed data

6. Reserve: Resource reservation must be sequential to avoid race conditions

7. Permit: Permit decisions must be made in order to maintain scheduling consistency

8. PreBind: Pre-binding operations must complete in order before binding

9. Bind: Only one bind plugin needs to succeed; they execute in order until one succeeds

10. PostBind: Post-binding cleanup executes sequentially

11. Unreserve: Cleanup must happen in reverse order of reservation

Why Sequential? These phases either:

Modify shared state that requires atomicity (Reserve, PreBind, Bind)

Make decisions that depend on previous plugin results (PreFilter, PostFilter)

Require deterministic ordering for correctness (QueueSort, Permit)

Parallel Execution Phases

The following extension points execute plugins in parallel across nodes:

Filter: Each node is evaluated independently, so filtering can happen concurrently

Score: Scoring each node is independent, enabling parallel execution

NormalizeScore: Score normalization runs in parallel for each plugin

Why Parallel? These phases involve per-node operations where each node evaluation is independent of others. The framework uses a `Parallelizer` that manages worker pools to execute these operations concurrently.

Implementation Details

From analyzing the framework code, here’s how parallel execution works:

// Score plugins run in parallel across nodes

f.Parallelizer().Until(ctx, len(nodes), func(index int) {

nodeInfo := nodes[index]

for _, pl := range plugins {

score, status := pl.Score(ctx, state, pod, nodeInfo)

// Store score for this node

}

}, metrics.Score)Performance Impact

This execution strategy provides significant performance benefits:

Filter Phase: In a 1000-node cluster, filtering can happen 16x faster with default parallelism

Score Phase: Scoring hundreds of nodes concurrently dramatically reduces scheduling latency

Sequential Phases: Minimal performance impact, as they typically do lightweight operations

The framework’s intelligent use of parallelism is why Kubernetes can scale to clusters with thousands of nodes while maintaining sub-second scheduling latency for most pods. This ensures that plugins can influence scheduling decisions at precisely the right moment, whether that’s early filtering, detailed scoring, or final binding decisions.

The parallel execution model relies heavily on efficient data sharing between plugins. The `CycleState` mechanism (covered in Section 8) enables the “write once, read many times” pattern that makes parallel Filter and Score execution both safe and performant.

5. How to Extend the Kubernetes Scheduler

The framework is designed to be extensible, allowing you to create custom scheduling logic without forking the Kubernetes codebase. There are two primary ways to extend the scheduler: 1) through configuration (enabling/disabling/configuring existing plugins) or 2) by creating custom out-of-tree plugins.

Method 1: Configuring Existing Plugins

The simplest way to customize scheduling behavior is by configuring existing plugins through a `KubeSchedulerConfiguration`:

apiVersion: kubescheduler.config.k8s.io/v1

kind: KubeSchedulerConfiguration

profiles:

- schedulerName: custom-scheduler

plugins:

# Enable/disable plugins at specific extension points

filter:

enabled:

- name: NodeResourcesFit

- name: NodeAffinity

disabled:

- name: TaintToleration

score:

enabled:

- name: NodeResourcesFit

weight: 10

- name: PodTopologySpread

weight: 5

pluginConfig:

# Configure individual plugins

- name: NodeResourcesFit

args:

scoringStrategy:

type: LeastAllocated

resources:

- name: cpu

weight: 1

- name: memory

weight: 1This approach allows you to:

Enable/disable specific plugins at each extension point

Adjust plugin weights for scoring

Configure plugin-specific parameters

Create multiple scheduler profiles with different configurations

Method 2: Creating Out-of-Tree Custom Plugins

For more sophisticated customization, you can create your own plugins. The Kubernetes community maintains an official repository of out-of-tree scheduler plugins at kubernetes-sigs/scheduler-plugins, which provides production-ready plugins (i.e., Capacity Scheduling, Coscheduling, Preemption Toleration, etc.).

These plugins serve as excellent references for building your own custom schedulers.

We will follow this blog with another one on how to create a custom plugin and configure it.

Method 3: Using Multiple Scheduler Profiles

One of the most powerful features of the Kubernetes scheduler framework is the ability to run multiple scheduler profiles within a single scheduler binary. This enables complex multi-tenancy, A/B testing, and workload-specific scheduling policies without deploying separate scheduler instances.

What Are Scheduler Profiles?

A scheduler profile is a named configuration that defines:

Which plugins are enabled at each extension point

Plugin-specific configuration (weights, parameters, etc.)

Performance settings (percentage of nodes to score)

One scheduler binary can run multiple profiles simultaneously. Each profile gets its own framework instance with its own plugin configuration, but they all share the same:

Scheduling queue

Cluster cache/snapshot

Client connections

Informers

How Pod-to-Profile Matching Works

Pods are matched to profiles via the `spec.schedulerName` field:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: my-pod

spec:

schedulerName: high-priority-scheduler # Matches this profile

containers:

- name: app

image: nginxHere is how this happens in the code:

func (sched *Scheduler) ScheduleOne(ctx context.Context) {

// Get next pod from queue

podInfo, err := sched.NextPod(logger)

pod := podInfo.Pod

// Match pod to the correct framework based on schedulerName

fwk, err := sched.frameworkForPod(pod)

if err != nil {

// Pod specifies unknown scheduler name

logger.Error(err, “Error occurred”)

return

}

// Schedule using the matched profile’s framework

scheduleResult, err := sched.SchedulePod(ctx, fwk, state, pod)

// ...

}The scheduler maintains a map of profiles:

type Scheduler struct {

// Profiles are the scheduling profiles

Profiles profile.Map // map[schedulerName]Framework

SchedulingQueue internalqueue.SchedulingQueue

Cache internalcache.Cache

// ...

}Now that we understand how to extend the scheduler, let’s explore the built-in plugins that come with Kubernetes.

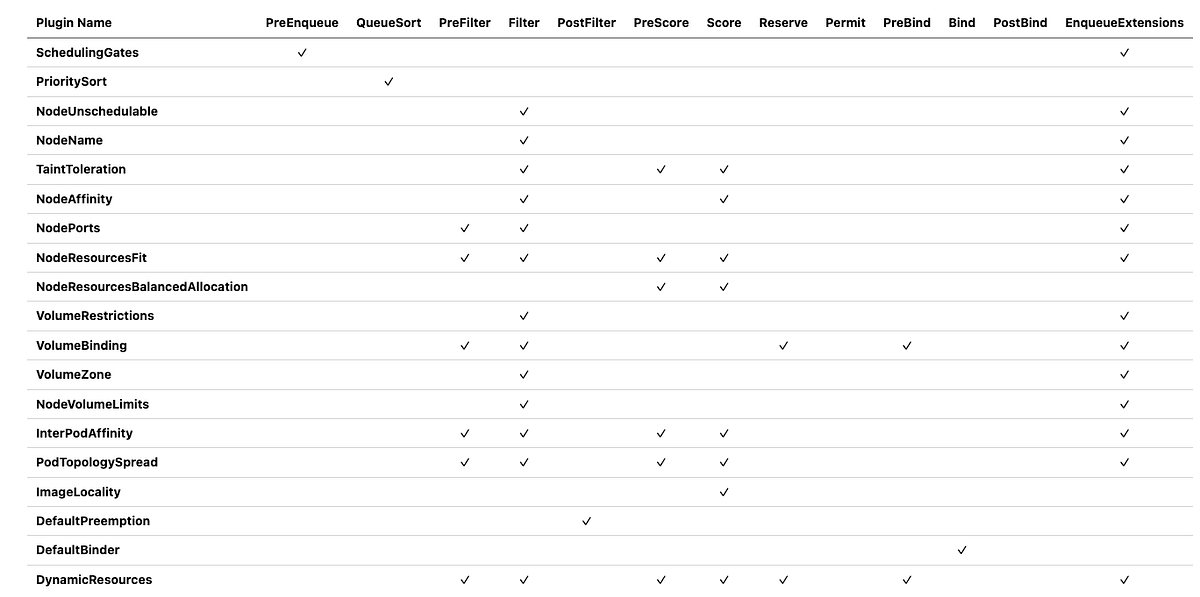

6. In-Tree Plugins

The Kubernetes scheduler comes with a comprehensive set of built-in plugins that handle various scheduling concerns. Let me walk you through each one, explaining what it does, how it works, and which extension points it implements. We will follow this blog with another one that will deep dive into the in-tree plugins in detail.

Extension Points Summary

Here‘s a comprehensive overview of which extension points each in-tree plugin implements:

Note: The EnqueueExtensions column indicates whether the plugin implements queueing hints to optimize pod re-queueing based on cluster events.

Default Plugin Configuration

By default, most plugins are enabled through the MultiPoint plugin set, which registers plugins at all their applicable extension points:

plugins:

multiPoint:

enabled:

- name: SchedulingGates

- name: PrioritySort

- name: NodeUnschedulable

- name: NodeName

- name: TaintToleration

weight: 3

- name: NodeAffinity

weight: 2

- name: NodePorts

- name: NodeResourcesFit

weight: 1

- name: VolumeRestrictions

- name: NodeVolumeLimits

- name: VolumeBinding

- name: VolumeZone

- name: PodTopologySpread

weight: 2

- name: InterPodAffinity

weight: 2

- name: DefaultPreemption

- name: NodeResourcesBalancedAllocation

weight: 1

- name: ImageLocality

weight: 1

- name: DefaultBinderThe weights determine the relative importance of each scoring plugin. The final node score is a weighted sum of all score plugin results.

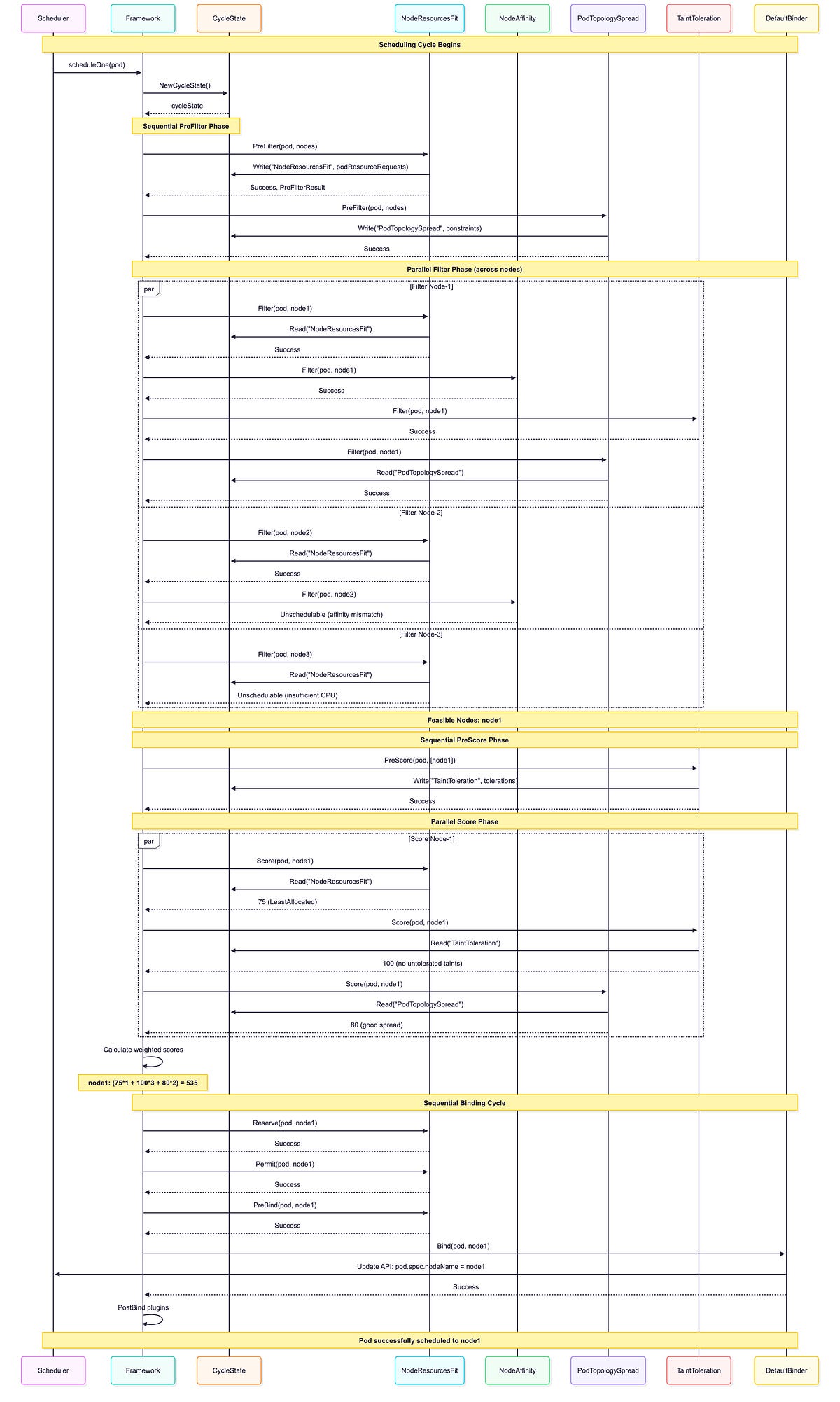

In-Tree Plugins Execution Sequence

This sequence diagram shows how in-tree plugins execute during an actual scheduling cycle, demonstrating the interaction between the framework, CycleState, and plugins:

7. Advanced Implementation Details: Why the Framework Works This Way

After analyzing the framework implementation extensively, I’ve discovered several sophisticated design decisions that explain why the framework works the way it does.

Plugin Interface Design Rationale

The framework uses interfaces rather than concrete types for plugins:

// Plugin interfaces are designed to be minimal and focused

// This allows for better testing, mocking, and composition

type Plugin interface {

Name() string

}

type PreFilterPlugin interface {

Plugin

PreFilter(ctx context.Context, state *CycleState, p *v1.Pod) *Status

}Using interfaces allows plugins to be tested in isolation and enables better composition of functionality. This design choice makes the framework more maintainable and testable.

Plugin Ordering Strategy

The framework maintains plugin order through slices rather than maps:

// Plugins are stored in ordered slices for each extension point

// This ensures deterministic execution order

type frameworkImpl struct {

preFilterPlugins []framework.PreFilterPlugin

filterPlugins []framework.FilterPlugin

scorePlugins []framework.ScorePlugin

// ... other ordered slices

}Using ordered slices ensures deterministic plugin execution order, which is crucial for reproducible scheduling behavior and debugging.

Conclusion

The Kubernetes scheduler framework is a masterpiece of software architecture. Its plugin system provides incredible flexibility while maintaining performance and consistency. Through this deep dive, we’ve explored:

Plugin Framework Architecture: A sophisticated orchestration system managing 12 extension points

Extension Points: Carefully designed hooks at precisely the right moments in the scheduling pipeline

Parallel vs Sequential Execution: Intelligent balancing of performance and correctness

Extensibility: Both configuration-based customization and custom plugin development

In-Tree Plugins: 19 built-in plugins handling diverse scheduling concerns.

What impressed me most during my analysis was how the framework balances flexibility with performance. The parallel execution at the Filter and Score phases, combined with the custom priority heap and assume cache, enables scaling to thousands of nodes while maintaining sub-second scheduling latency.

The extension points are carefully designed to provide hooks at exactly the right moments in the scheduling process, allowing plugins to influence decisions without disrupting the core scheduling logic.

Whether you’re customizing existing plugins or building entirely new ones, the framework provides the tools, patterns, and performance characteristics needed for scheduling behavior in clusters ranging from a few nodes to thousands.

In the next post, I’ll dive into the In-Tree plugins, followed by a dedicated blog on how to extend and customize the scheduler.

Resources

Repository for out-of-tree scheduler plugins based on scheduler framework. - kubernetes-sigs/scheduler-pluginsgithub.com

FEATURE STATE: Kubernetes v1.19 [stable] The scheduling framework is a pluggable architecture for the Kubernetes…kubernetes.io

Appendix: Additional Diagrams

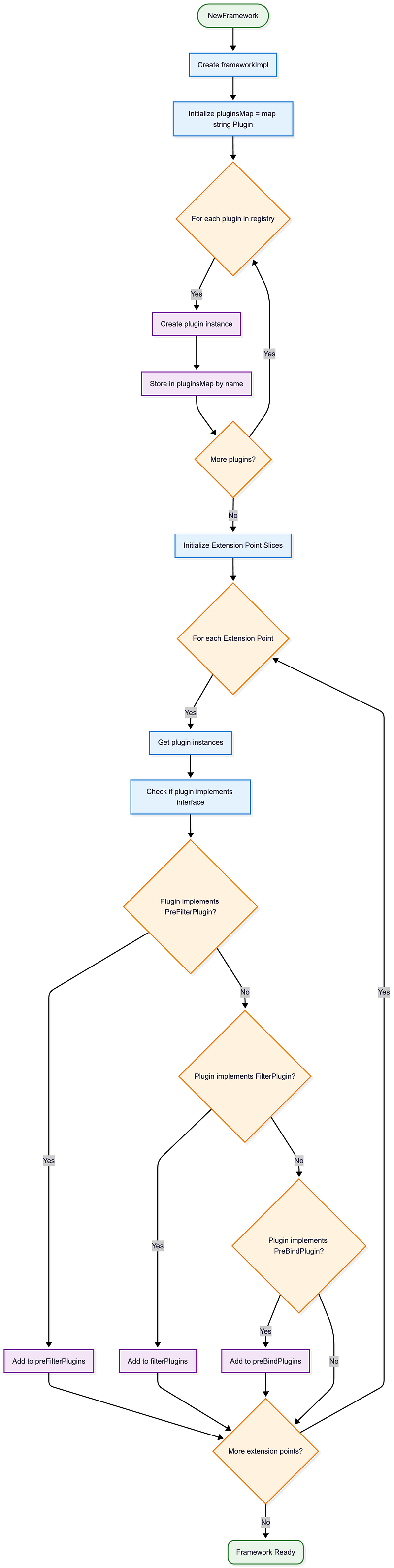

Framework Initialization Flowchart

This detailed flowchart shows the framework initialization process:

This analysis is based on Kubernetes v1.35.0-alpha.0 codebase. The framework continues to evolve, but the core architectural principles remain consistent across versions.