Kubernetes Scheduler Queue Management

The Art of Pod State Transitions

This is the fifth in a series of blog posts exploring the Kubernetes kube-scheduler from the perspective of someone who has dug deep into the codebase.

Introduction

Today, we want to dive deep into the Scheduling Queue, one of the most fascinating components of the scheduler. Where unscheduled pods wait to be processed and run. But it’s not just a simple queue; it’s a state machine that manages pod lifecycles, handles failures gracefully, and responds to cluster events. Understanding how this works is crucial for anyone who wants to understand scheduler behavior or troubleshoot scheduling issues.

The Three-Queue Architecture

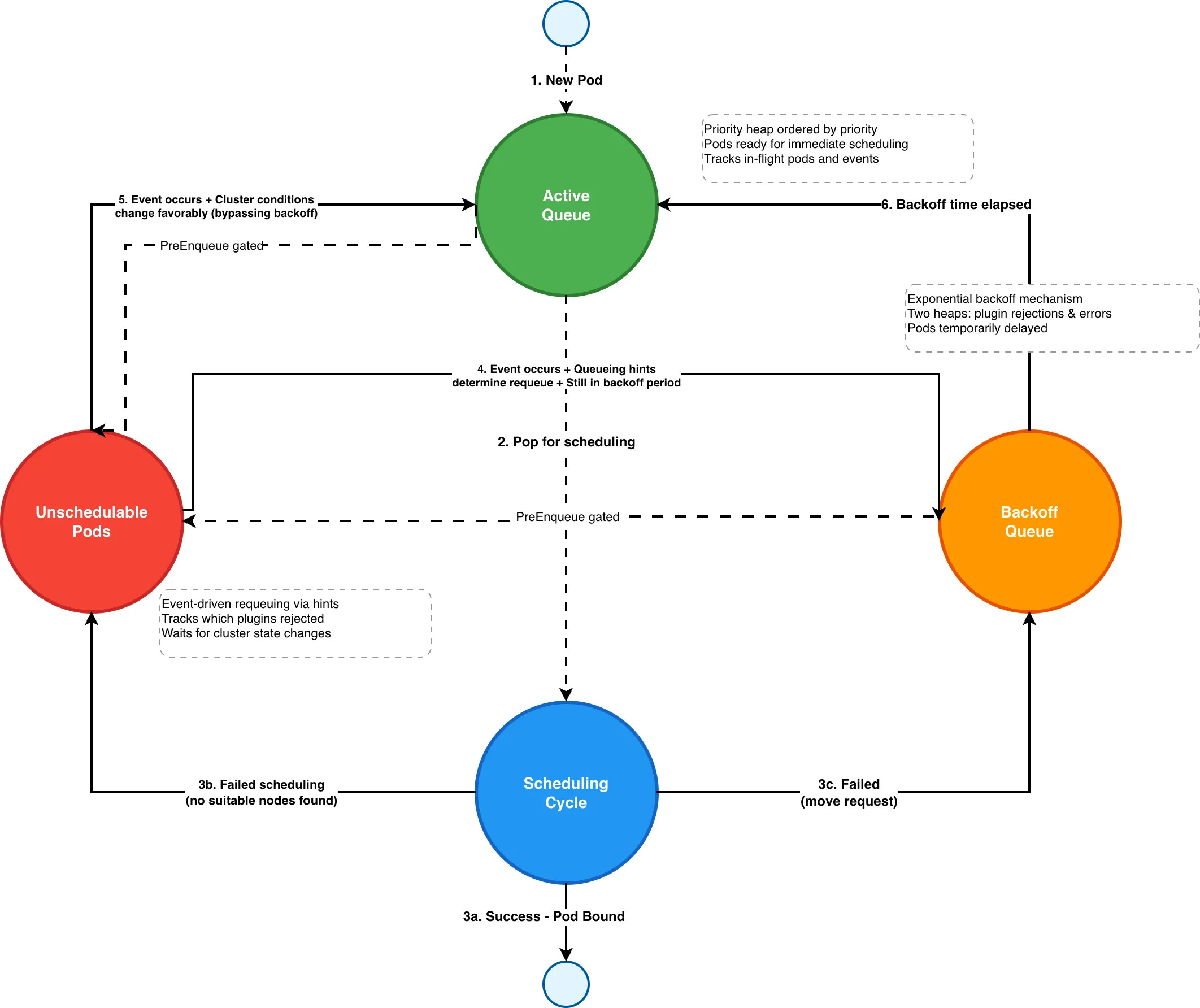

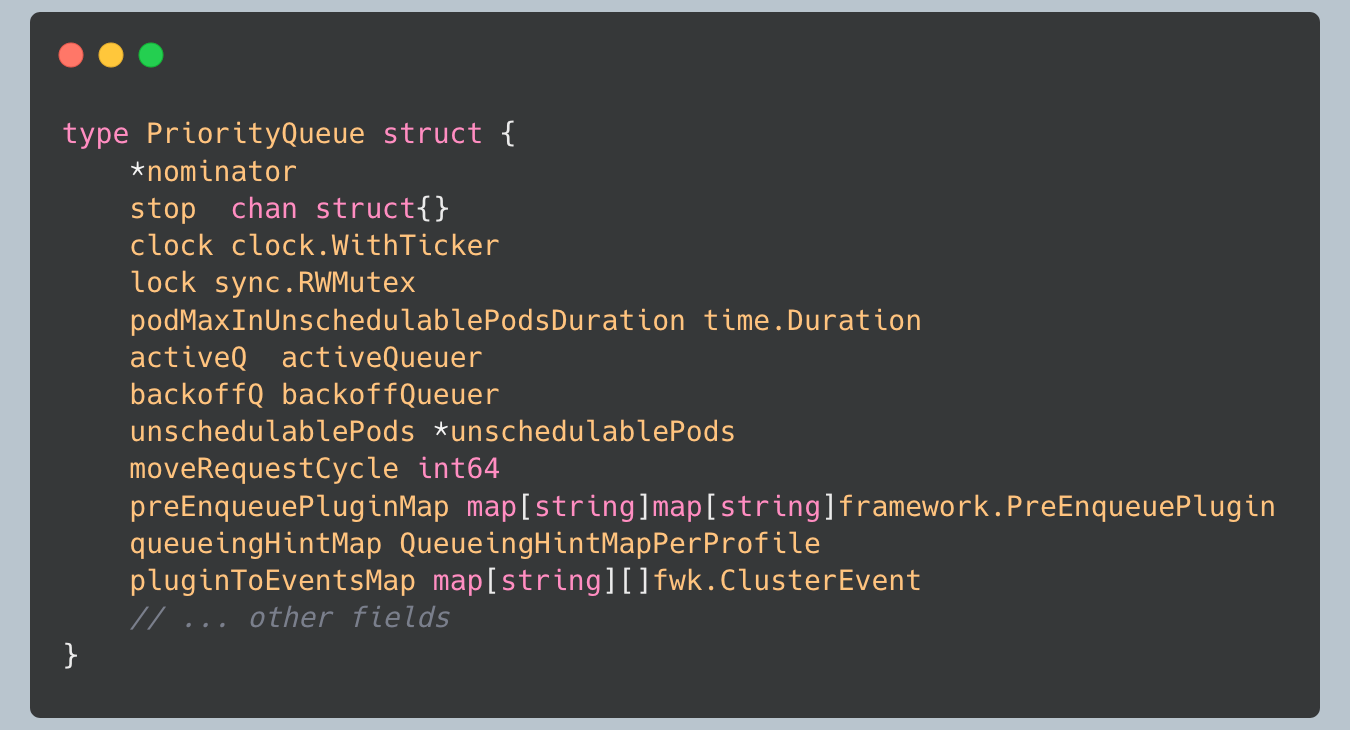

From examining the queue implementation and tracing the scheduler’s operational flow, I discovered that the scheduling queue is far more sophisticated than a simple FIFO queue. It implements a sophisticated three-queue architecture that manages pods through different states based on their scheduling history and cluster conditions.

The queue consists of three distinct sub-queues, each serving a specific purpose in the pod lifecycle:

ActiveQ: Holds pods that are being considered for scheduling - these are pods ready to be processed by the scheduler

BackoffQ: Holds pods that moved from unschedulablePods and will move to activeQ when their backoff periods complete - these are pods temporarily delayed due to previous scheduling failures

UnschedulablePods: Holds pods that were already attempted for scheduling and are currently determined to be unschedulable, these are pods waiting for cluster conditions to change

This architecture enables sophisticated state transitions, allowing pods to move between queues based on cluster events, backoff periods, and scheduling hints from plugins.

Queue State Transitions: The Pod Lifecycle Journey

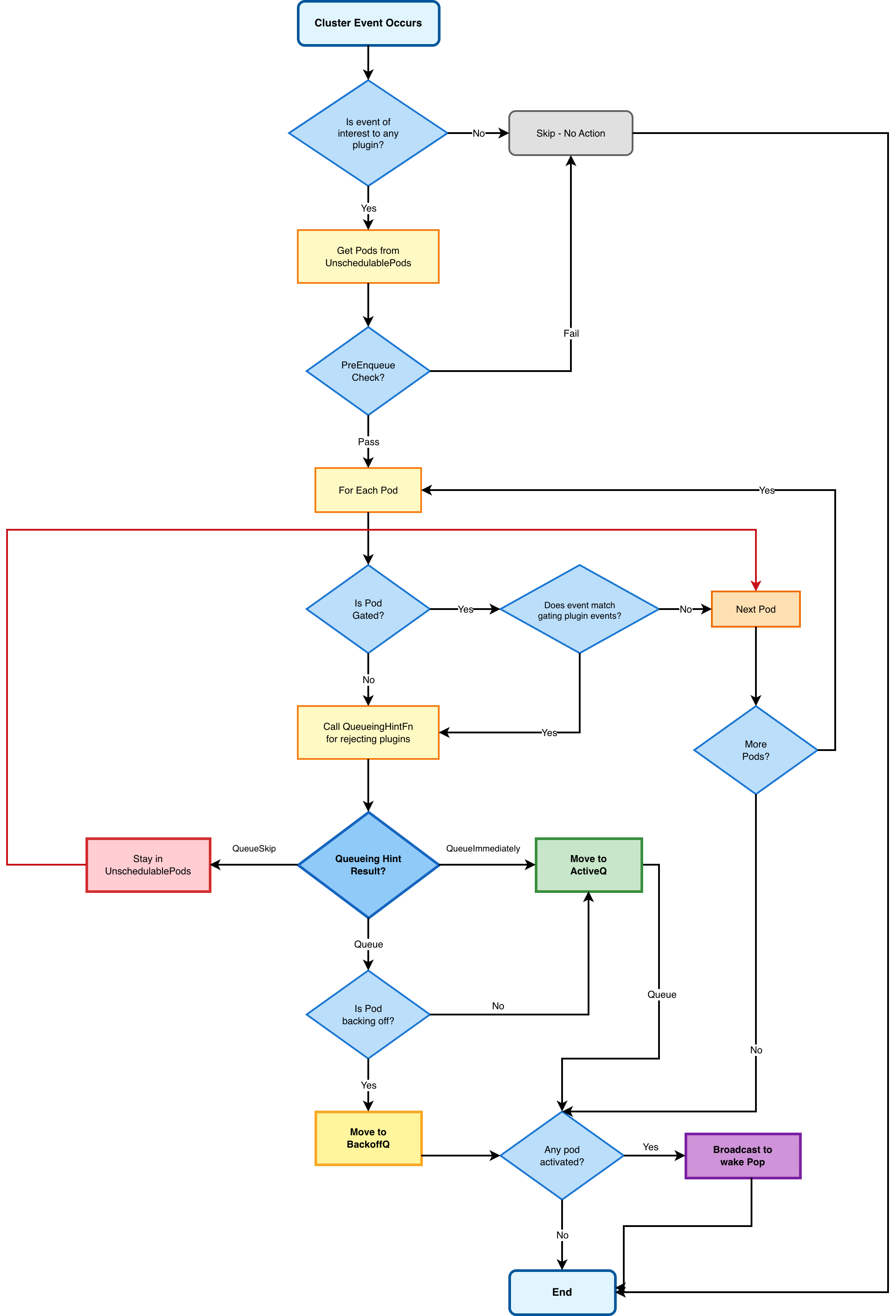

Pods move through the queue system in a sophisticated state machine with three main state transitions between them:

The Three-Queue State Machine

ActiveQ → UnschedulablePods: When a pod fails scheduling (no suitable nodes found), it moves to UnschedulablePods, waiting for cluster conditions to change.

UnschedulablePods → BackoffQ: When a relevant cluster event occurs, and queueing hints determine the pod should be requeued, it moves to BackoffQ if still within its backoff period for a temporary delay before retry.

BackoffQ → ActiveQ: When the backoff time expires, the pod is moved back to ActiveQ for another scheduling attempt.

UnschedulablePods → ActiveQ: A node event can directly move a pod from UnschedulablePods to ActiveQ, bypassing the backoff mechanism when cluster conditions change favorably.

This state machine ensures that pods are retried, avoiding unnecessary scheduling attempts while responding quickly to cluster changes that might make previously unschedulable pods schedulable.

The following diagram illustrates the pod lifecycle through the three-queue system:

Active Queue: The Main Processing Pipeline

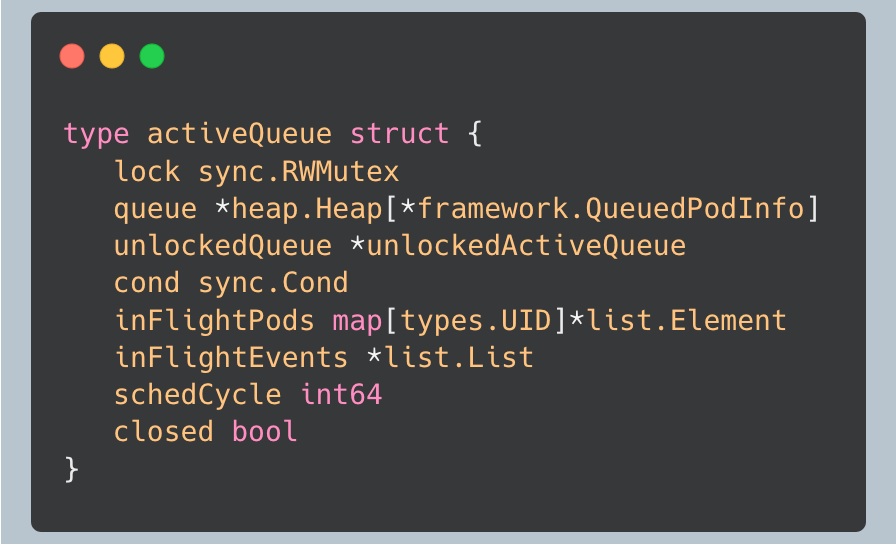

The active queue is where pods wait to be scheduled. It’s implemented as a priority heap, ensuring that the highest priority pods are processed first.

What’s particularly interesting about the active queue is how it tracks in-flight pods. The `inFlightPods` map maintains a record of all pods currently being processed, along with the events that occurred during their processing. This is crucial for maintaining consistency and handling edge cases.

The queue uses a condition variable (`cond`) to notify waiting goroutines when new pods are added efficiently. This design allows the scheduler to block efficiently while waiting for work, rather than busy-waiting. The condition variable is critical in the context of the queue’s locking hierarchy, ensuring that goroutines can wait for work without holding locks.

Backoff Queue: Graceful Failure Handling

The backoff queue is where pods go when they fail to schedule. It implements a sophisticated backoff mechanism that prevents failed pods from consuming excessive resources.

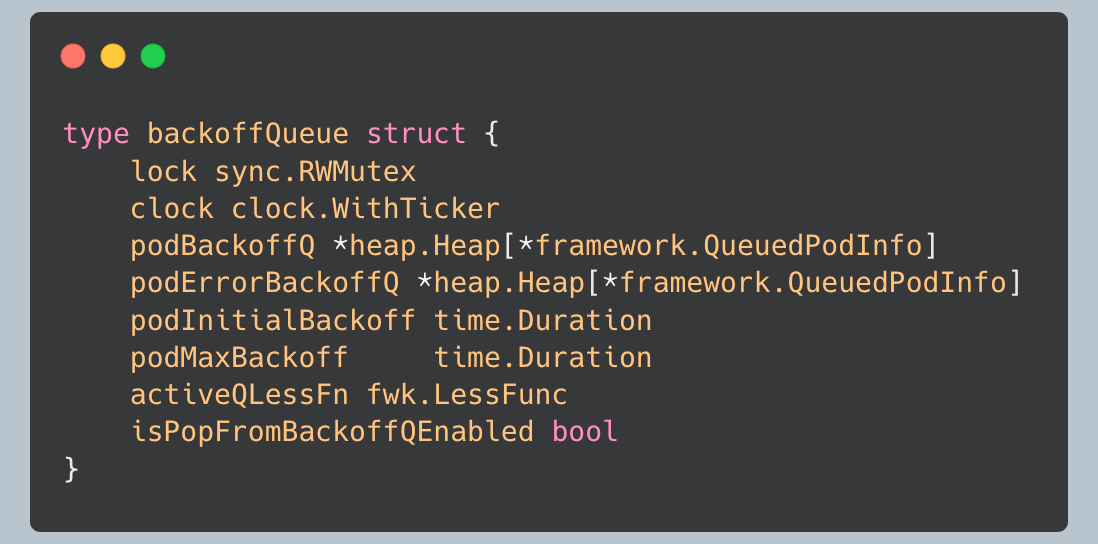

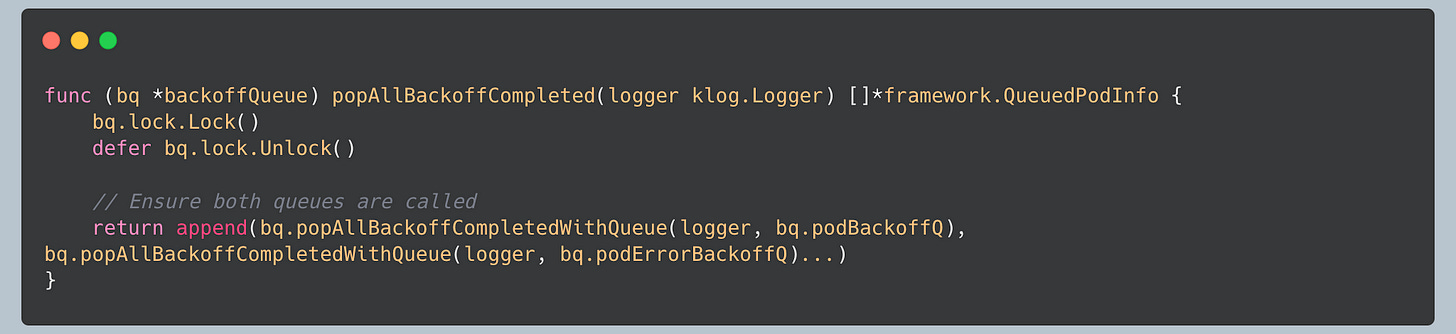

The backoff queue actually maintains two separate heaps:

podBackoffQ: For pods that failed due to resource constraints or plugin rejections

podErrorBackoffQ: For pods that failed due to errors

This distinction is important because error-based failures might need different handling than constraint-based failures.

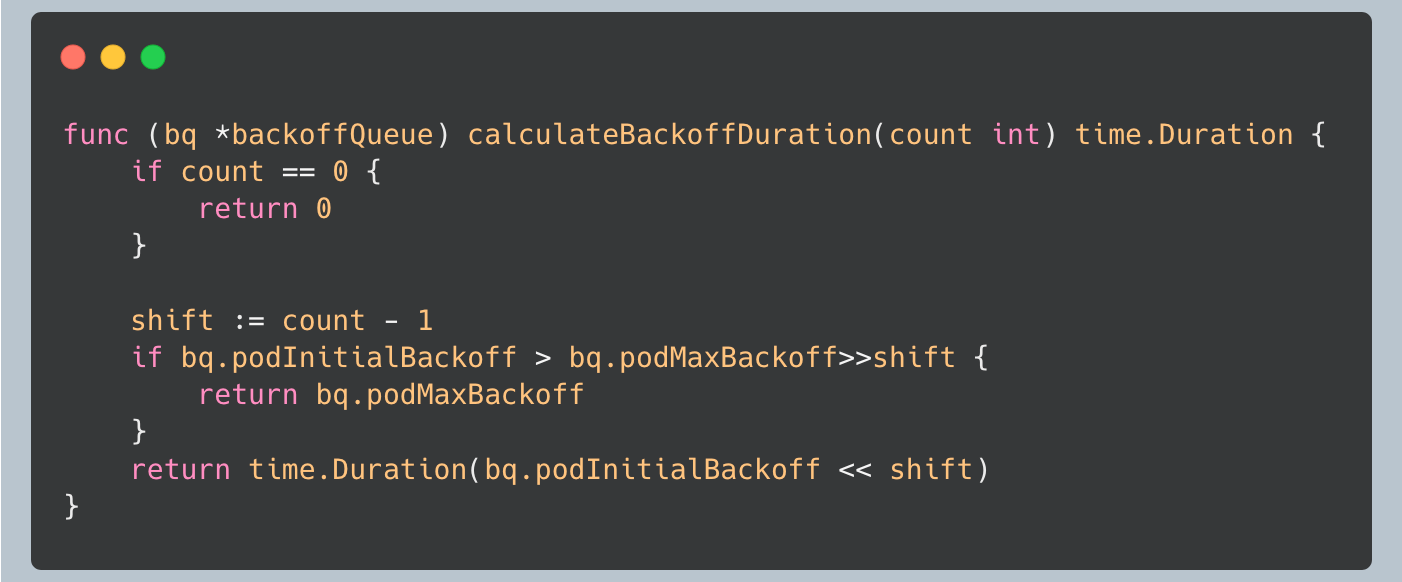

Backoff Calculation: Exponential Backoff with Windows

The backoff calculation is particularly sophisticated. After analyzing the implementation, I was impressed by how it balances fairness with efficiency:

The backoff duration follows an exponential backoff pattern: `initialBackoff * 2^(attempts-1)`, capped at `maxBackoff`. This ensures that pods that consistently fail don’t consume excessive resources, while still giving them opportunities to succeed.

The queue also implements a windowing mechanism to align backoff expiration times, which improves efficiency by allowing multiple pods to be processed together.

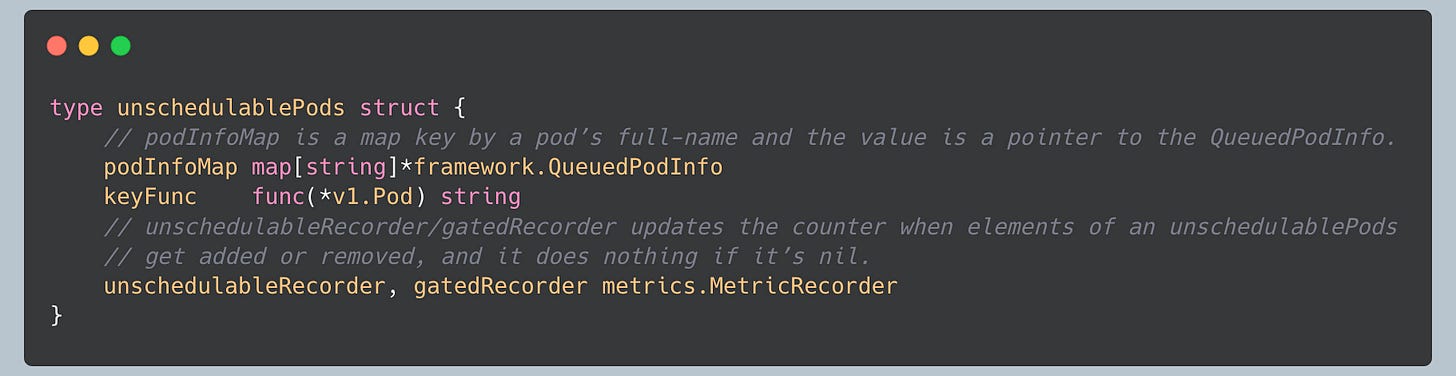

Unschedulable Pods: The Waiting Room

The unschedulable pods collection is where pods wait when they can’t be scheduled due to current cluster conditions. This is different from the backoff queue; these pods aren’t necessarily failed, they’re just waiting for conditions to change.

The unschedulable pods collection maintains a map of pod information, allowing for efficient lookups and updates. It also tracks which plugins rejected each pod, which is crucial for the event-driven requeuing logic. The two separate metric recorders track unschedulable pods and gated pods (those blocked by PreEnqueue plugins) independently.

Event-Driven Pod Movements: The Queue’s Intelligence

One of the most sophisticated aspects of the queue is its response to cluster events. The queue implements requeuing logic that prevents unnecessary work while ensuring pods get scheduled when conditions change. With the introduction of asynchronous preemption (promoted to beta in v1.33), the queue now handles preemption operations more efficiently, allowing the scheduler to continue processing other pods while preemption is in progress.

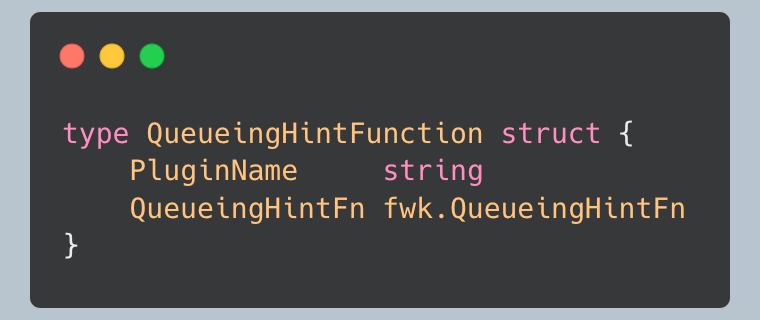

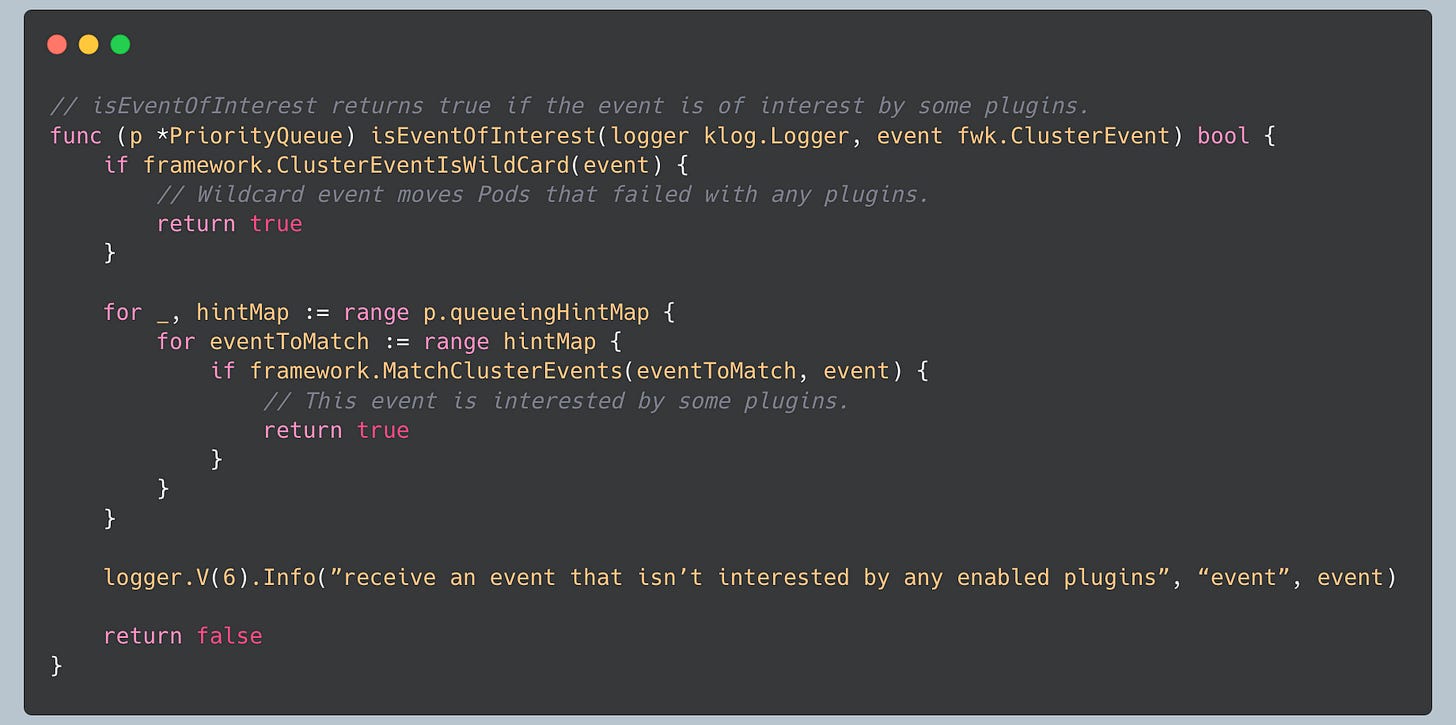

Queueing Hints: Smart Requeuing Logic

The queue implements queueing hints system that allows plugins to indicate whether specific events should trigger pod requeuing:

Plugins can implement `QueueingHintFn to suggest whether a cluster event should cause a pod to be requeued. The function can return:

QueueSkip: The event doesn’t affect this pod

Queue: The event might make the pod schedulable

QueueImmediately: The event definitely makes the pod schedulable

This system is particularly clever because it allows plugins to provide domain-specific knowledge about when cluster changes might resolve their rejections.

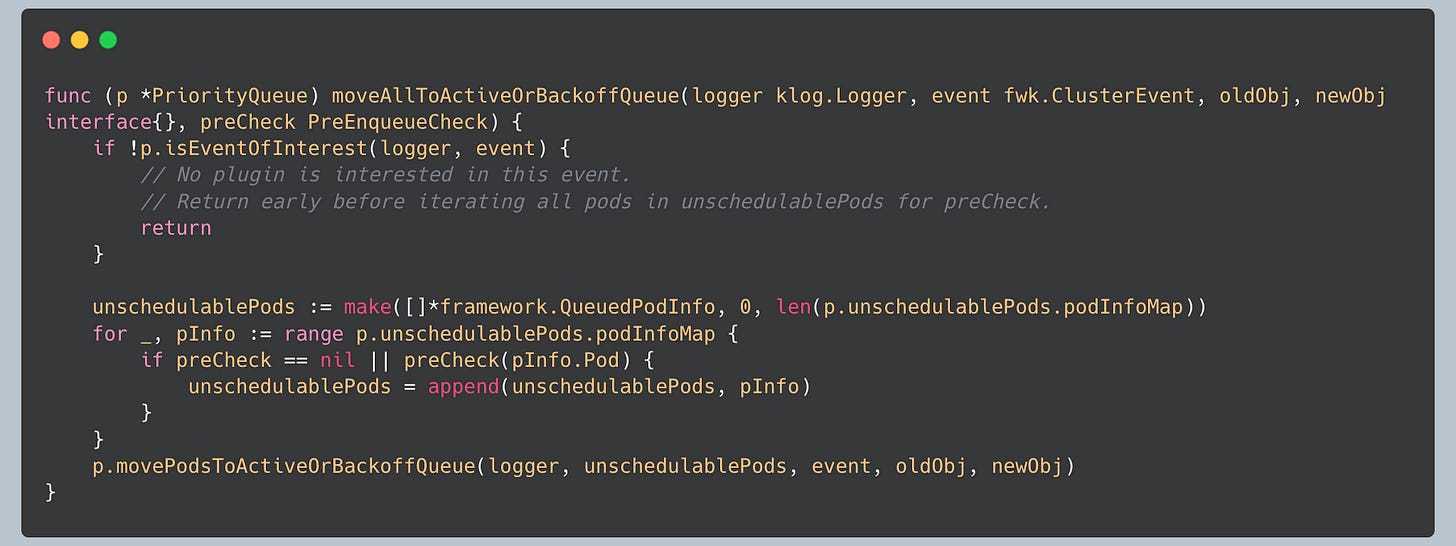

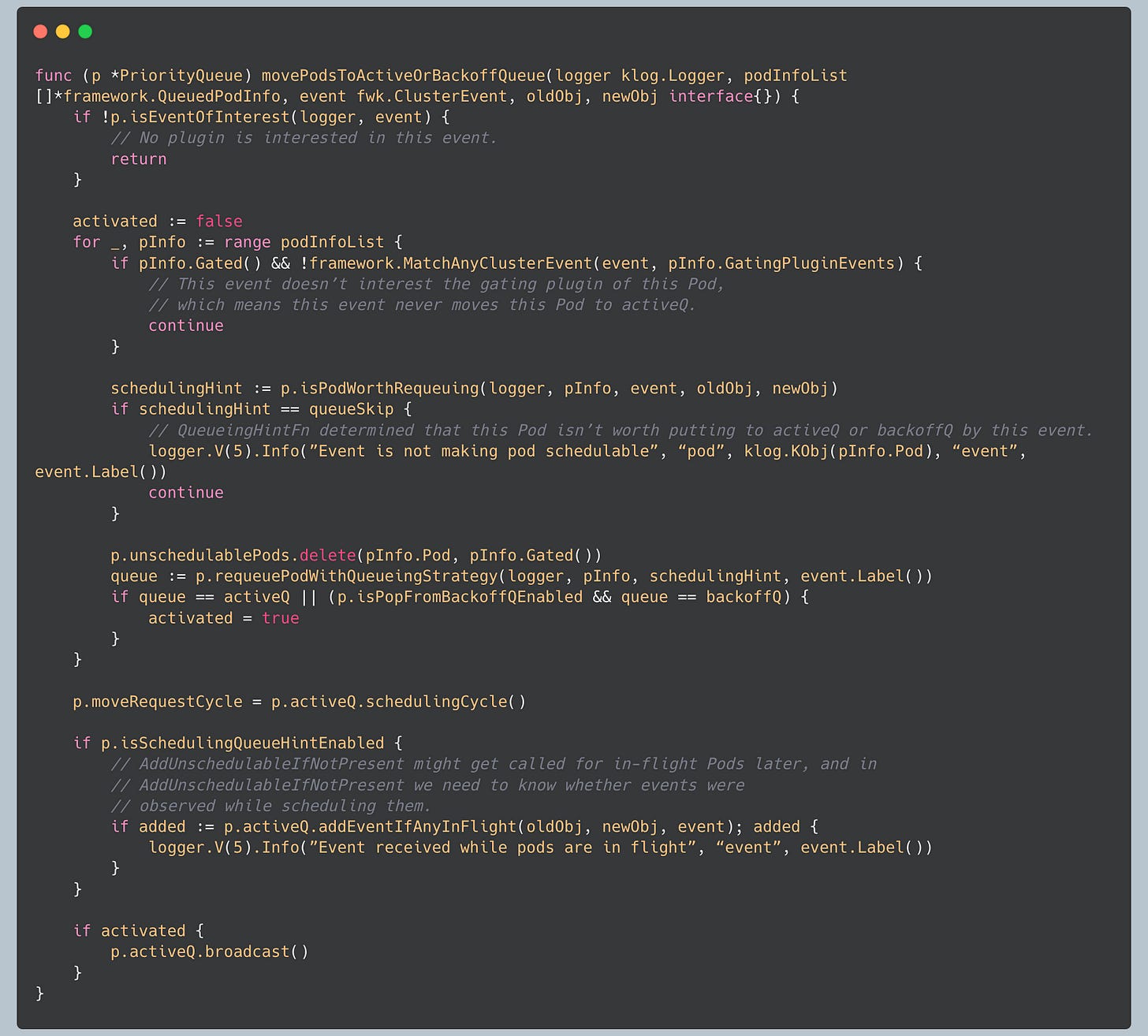

Event-Driven Requeuing Flow

The following diagram shows how cluster events trigger pod requeuing through the queueing hints system:

Event Processing: Movement Decisions

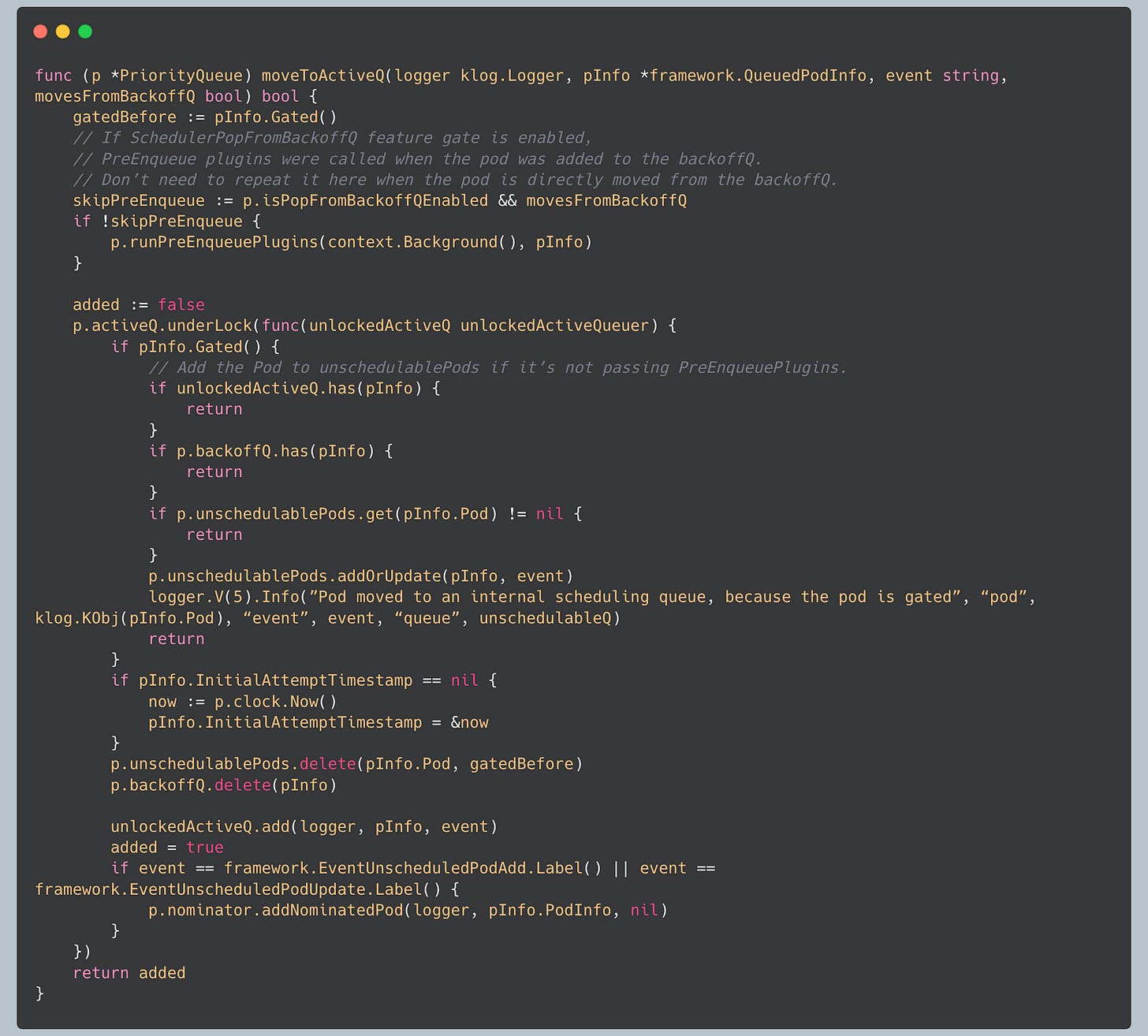

When cluster events occur, the queue processes them:

The queue first checks if any plugins are interested in the event. If not, it skips processing entirely to avoid unnecessary work. Then it evaluates each unschedulable pod to determine if the event should trigger requeuing.

Pod State Transitions: A Complex Dance

The queue manages complex state transitions between its three sub-queues. Let me walk through a typical pod lifecycle:

Initial Addition: A new pod is added to the active queue

Scheduling Attempt: The pod is popped from the active queue and processed

Failure Handling: If scheduling fails, the pod moves to either:

Backoff queue (if it failed due to constraints)

Unschedulable pods (if they failed due to the current cluster state)

Event-Driven Movement: Cluster events can move pods from unschedulable to active or backoff queues

Backoff Completion: Pods in the backoff queue move to the active queue when their backoff period expires

Success: Successfully scheduled pods are removed from all queues

PreEnqueue Plugins: The Gatekeepers

The queue integrates with the framework’s PreEnqueue plugins, which act as gatekeepers before pods enter the active queue:

PreEnqueue plugins can gate pods, preventing them from entering the active queue. Gated pods are moved to the unschedulable pods collection, where they wait for conditions to change.

Concurrency and Thread Safety: The Queue’s Robustness

The queue implementation is highly concurrent, with multiple goroutines accessing it simultaneously. After analyzing the locking strategy, I was impressed by the sophisticated approach to thread safety.

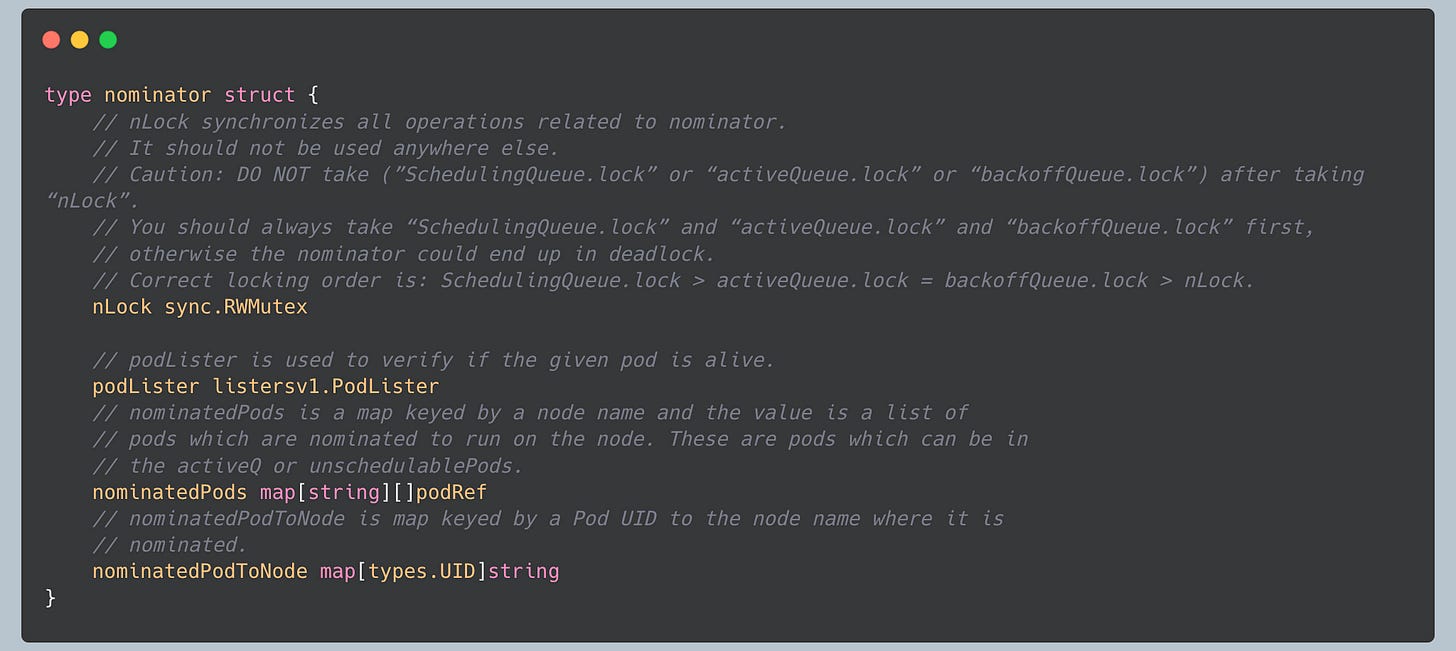

Locking Hierarchy: Preventing Deadlocks

The queue implements a strict locking hierarchy to prevent deadlocks. This hierarchy ensures that locks are acquired in the same order, preventing deadlocks. The comments in the code emphasize this ordering, showing the careful attention to concurrency safety.

Condition Variables: Efficient Waiting

The queue uses condition variables to notify waiting goroutines efficiently. When pods are added to the active queue, the condition variable is signaled, waking up any goroutines waiting for work. This is much more efficient than busy-waiting or polling.

In-Flight Tracking: Maintaining Consistency

The queue maintains detailed tracking of in-flight pods. This tracking is crucial for maintaining consistency during pod processing. The queue can track which events occurred during a pod’s processing and handle them appropriately when the pod completes.

Performance Optimizations: Making It Fast

The queue implementation includes several performance optimizations that I found particularly clever:

Event Interest Filtering

Before processing cluster events, the queue checks if any plugins are interested in them:

This filtering prevents unnecessary work when events occur that no plugins care about.

Batch Processing

The queue processes multiple pods together when possible, reducing the overhead of individual operations:

By batching operations and only broadcasting once at the end, the queue reduces the overhead of notifying waiting goroutines.

Metrics Integration

The queue integrates with the metrics system to provide visibility into its operation:

metrics.SchedulerQueueIncomingPods.WithLabelValues(”backoff”, event).Inc()This allows operators to monitor queue behavior and identify potential issues.

Error Handling and Recovery: Graceful Degradation

The queue implements sophisticated error handling and recovery mechanisms:

Pod Update Handling

When pods are updated, the queue handles the updates:

The queue handles pod updates in all three sub-queues, ensuring consistency across the entire system.

Backoff Queue Management

The backoff queue manages pods that have completed their backoff periods:

This function efficiently processes all pods that have completed their backoff periods, moving them back to the active queue.

The Nominator: Tracking Preempted Pods

The queue includes the “nominator” component that tracks pods that have been preempted:

The nominator maintains information about pods nominated to run on specific nodes (typically after preemption). The `nominatedPods` map uses lightweight `podRef` structs (containing just name, namespace, and UID) rather than full PodInfo objects for efficiency. The `nLock` is placed first, following the locking hierarchy conventions. This information is used by the scheduler to make informed decisions about preemption and to track the state of nominated pods.

Advanced Queue Management: Race Conditions and Edge Cases

After analyzing the queue implementation extensively, I’ve discovered several critical race conditions and edge cases that the queue handles to ensure reliable operation.

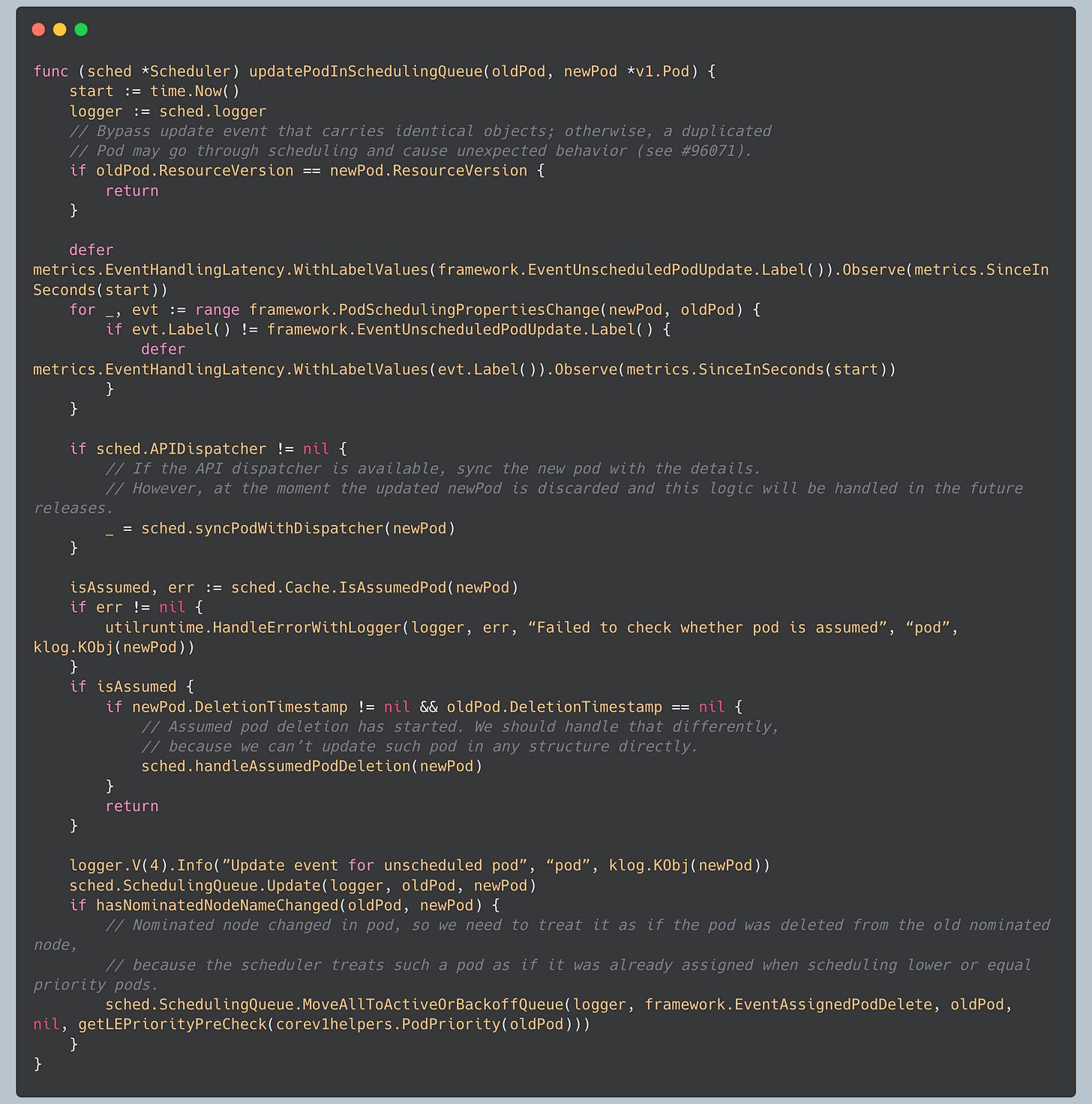

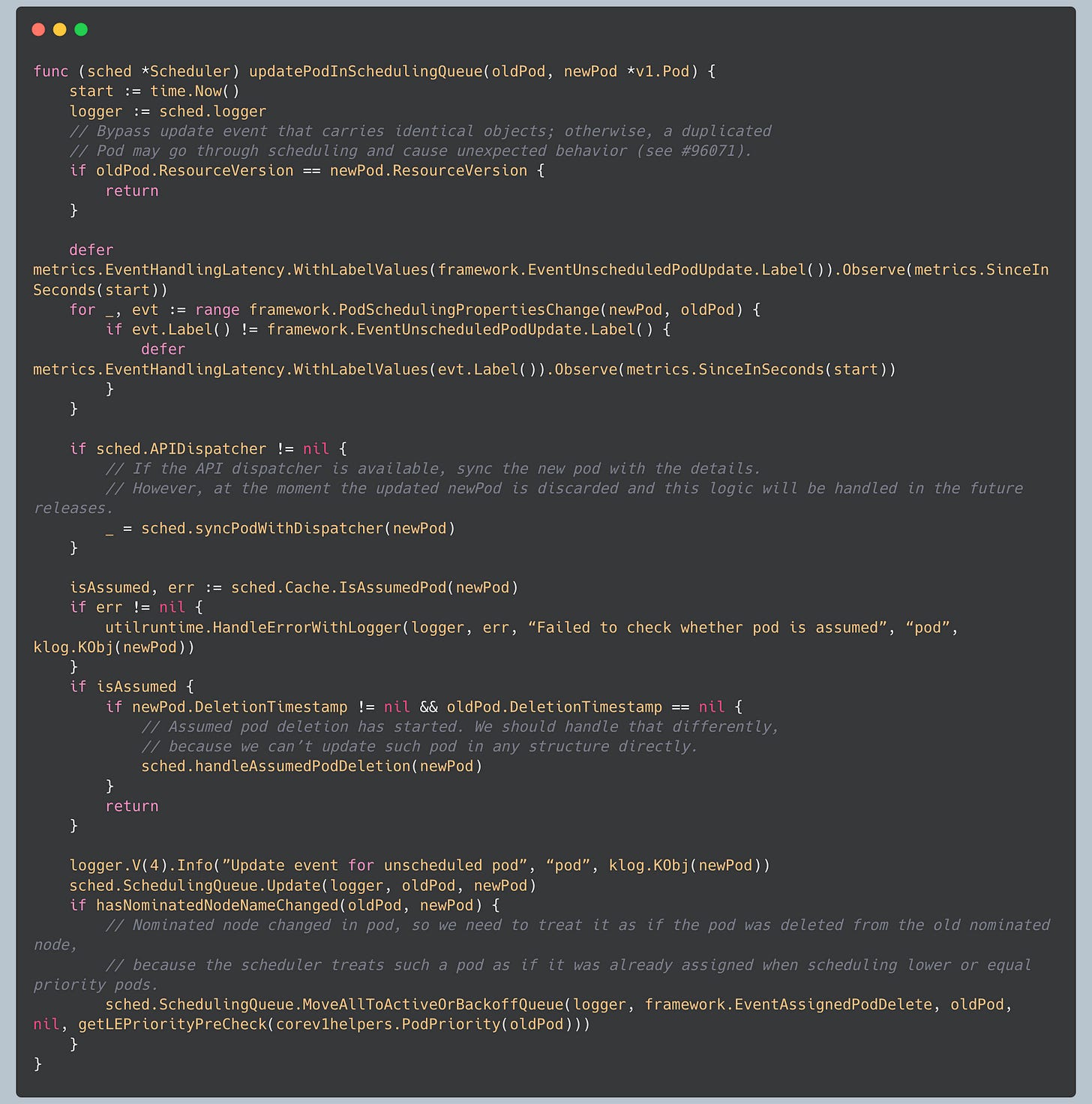

Pod Update Race Condition Prevention

The queue implements logic to prevent duplicate scheduling attempts:

The scheduler explicitly checks `ResourceVersion` to avoid duplicate scheduling attempts. This prevents a subtle bug where identical pod updates could cause pods to be scheduled multiple times. The full implementation can be found in `pkg/scheduler/eventhandlers.go`.

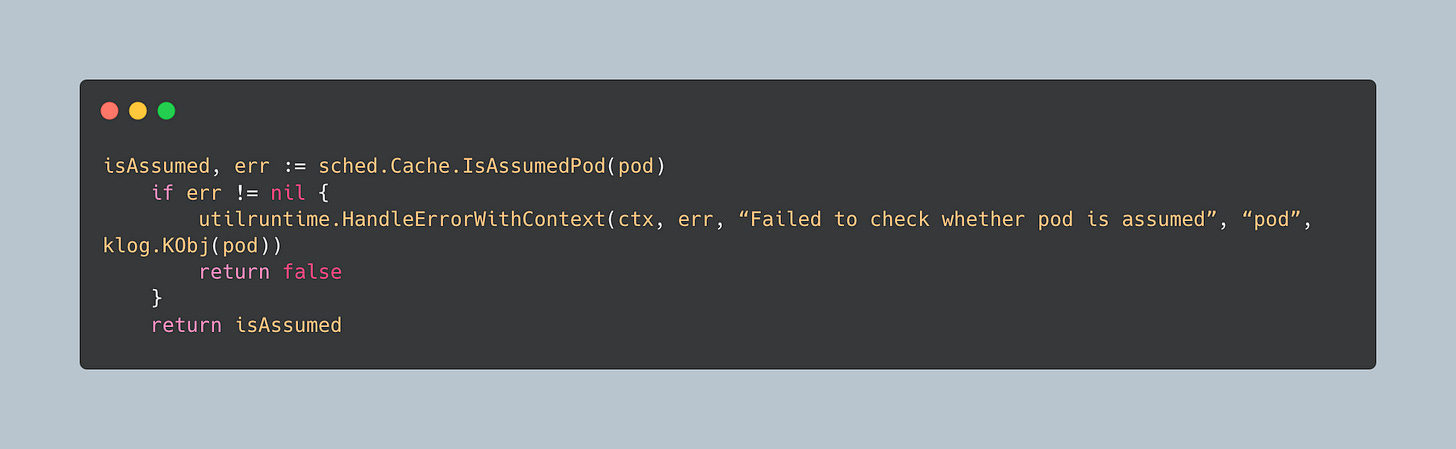

Assumed Pod State Race Prevention

The queue must check if a pod is already assumed before processing updates:

The scheduler must check if a pod is already assumed before processing updates. This prevents race conditions where a pod update arrives while the pod is in the middle of being bound.

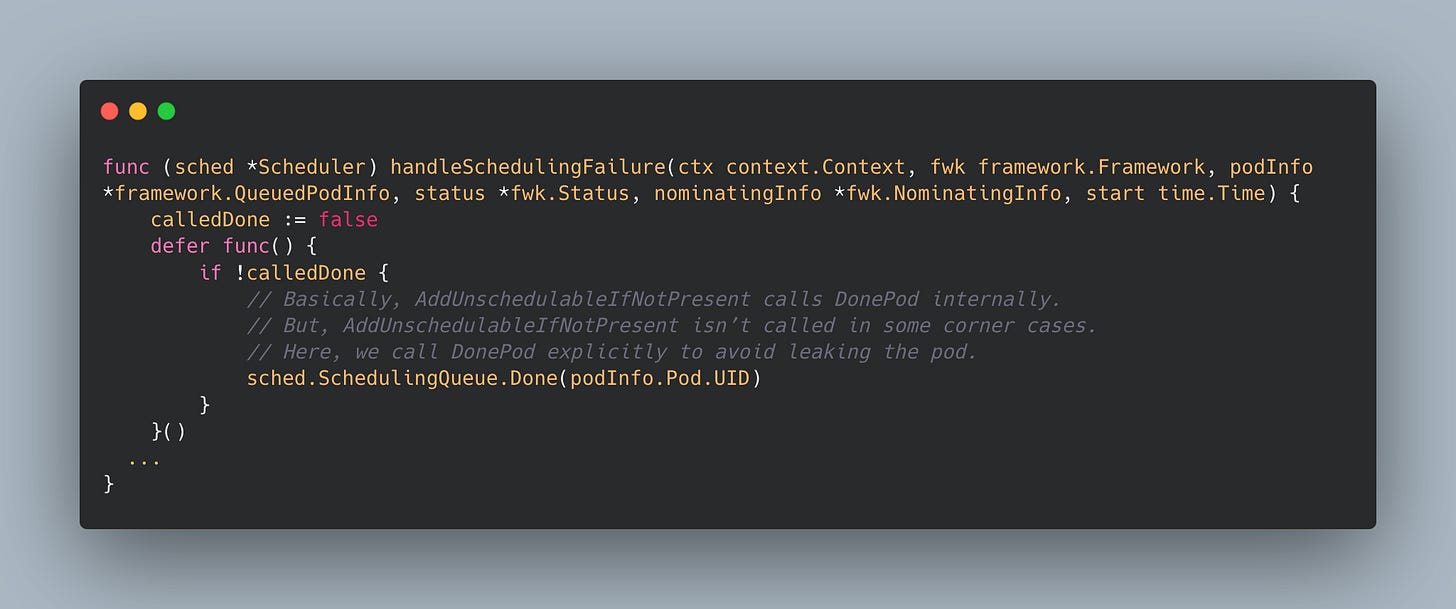

Pod Leak Prevention

The queue uses deferred functions to ensure pods are properly cleaned up even in error cases. This prevents pod leaks in the queue:

In upcoming blogs, we will continue our deep dive into the kube-scheduler's cycles, cache, and API dispatcher. Stay tuned!

This analysis is based on Kubernetes v1.35.0-beta codebase. The queue continues to evolve, but the core architectural principles remain consistent across versions.